Biologists see ultrafast recycling of neurotransmitter-filled bubbles

University of Utah and German biologists have discovered how nerve cells recycle tiny bubbles or “vesicles” that send chemical nerve signals from one cell to the next. The process is much faster and different than two previously proposed mechanisms for recycling the bubbles.

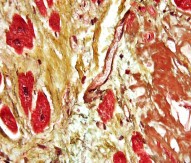

Researchers photographed mouse brain cells using an electron microscope after flash-freezing the cells in the act of firing nerve signals. That showed the tiny vesicles are recycled to form new bubbles only one-tenth of a second after they dump their cargo of neurotransmitters into the gap or “synapse” between two nerve cells or neurons.

University of Utah biologist Erik Jorgensen, senior author of the study, said: “Without recycling these containers or ‘synaptic vesicles’ filled with neurotransmitters, you could move once and stop, think one thought and stop, take one step and stop, and speak one word and stop.”

He added: “A fast nervous system allows you to think and move. Recycling synaptic vesicles allows your brain and muscles to keep working longer than a couple of seconds. This process also may protect neurons from neurodegenerative diseases like Lou Gehrig’s disease and Alzheimer’s. So understanding the process may give us insights into treatments someday.”

A brain cell maintains a supply of 300 to 400 vesicles to send chemical nerve signals, using up to several hundred per second to release neurotransmitters, said the study’s first author Shigeki Watanabe.

Recycling vesicles is called ‘endocytosis’. Jorgensen and Watanabe named the process they observed ‘ultrafast endocytosis’. They showed it takes one-tenth of a second for a vesicle to be recycled, and such recycling occurs on the edge of active zone – the place on the end of the nerve cell where the vesicles first unload neurotransmitters into the synapse between brain cells.

The study was published in the journal Nature.