Fruit flies work together to avoid CO2

Fruit flies respond more effectively to danger when in a group according to a research team from Switzerland’s EPFL and Université de Lausanne.

Scientists receiving funding from the European Research Council, amongst others, discovered the behaviour whilst studying the species. They also uncovered the neural circuits that relay this information.

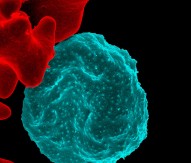

Flies exposed to a stress signal when in a group adopt a more effective response than isolated insects, according to the scientists. The insects are typically solitary dipterans, but interact to generate a coherent collective response.

To explore this behaviour, the researchers began by quantifying the presence of CO2 avoidance strategies. This gas represents a danger signal to the flies. A drosophila flying alone makes little effort to avoid the aversive odour, yet in a group, a significant proportion of flies leave the area within a few seconds.

Even deprived of their sense of smell, flies in a community with unmodified peers continue to go quickly to the good, clean air. By observing the flies, the researchers found that this group behaviour was preceded by numerous close contacts between the insects. Specifically, it is through small touches on the legs that the avoidance behaviour is strengthened. Previous data from the study suggested the critical role of receptors on limbs. Using various methods, including desensitising different parts of a limb, the researchers have been able to identify the applicable gene and locate the precise area of contact.

Speaking about the findings, Pavan Ramdya, lead author of a paper on the subject, said: “The identification of sensory pathways that govern collective response in drosophila could elucidate the dynamics of other animal groups such as schools of fish, migratory birds and even human crowds.”

The findings are posted in the journal Nature.