Aalto University

H2020′s Knowledge and Innovation Communities

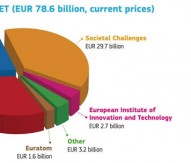

Encouraging greater research collaboration is a key objective of Horizon 2020. The next research and innovation framework programme will see the creation of six new Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KICs) as the budget for the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) is increased to €2.8bn between 2014 and 2020.

Professor Seija Kulkki of Aalto University School of Business is the founding director of one of Europe’s first KICs, the Centre for Knowledge and Innovation Research (CKIR). Whilst Kulkki is enthusiastic about the creation of more KICs in Europe, she has increasing concerns about budget cuts to Horizon 2020 and the consequential diminishing investment in growth and jobs in Europe.

How do you see knowledge and innovation-driven growth playing a role in Europe?

Knowledge and innovation-driven growth is the key for Europe’s future – this was recognised by Finland in the late 1990s.

Working with high-tech, knowledge-intensive Finnish firms, including Nokia, the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation (Tekes) initiated the CKIR at Aalto University School of Business in 1999. CKIR conducts scientific research on knowledge and innovation-driven growth and development from the viewpoints of firms, public agencies, technology and the society. Disciplines at CKIR include management and organisation sciences, service sciences, computer sciences and sciences on psychology, cognition and emotion. The strategic interdisciplinary research agenda of CKIR was developed with Professors James G March (Stanford University, USA), Ikujiro Nonaka (Hitostubashi University, Japan) and Yves Doz (INSEAD, France).

Since 2003, CKIR has been active in EU-funded projects, and currently co-ordinates the Future Internet public-private partnership (PPP). In 2006, CKIR also helped Finland’s EU Presidency and the European Commission create the European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL), a European-wide network of open innovation ecosystems where firms, public agencies, academia and people co-create new solutions tackling societal challenges, including wellbeing services, energy efficiency, smart city development, open public data and social media. ENoLL has identified over 300 open innovation ecosystems in Europe that are capable of conducting cross-border RDI projects together. ENoLL focuses on thematic, European-wide, pre-market experimentation and piloting in RDI – it tries to incorporate technology development and corporate RDI, as well as social sciences and humanities, in order to solve the societal challenges of our time.

Currently, Aalto University, with Nokia and VTT, participate in ICT Labs, one of the first three KICs of the EIT. ICT Labs is active in Paris, Berlin, Eindhoven, Stockholm, Helsinki and Trento. The focus areas include: Enabling Mobile Data Expansion, Smart Spaces and Ubiquitous Interaction, Green ICT for Ecological Sustainability, Big Data and Service Design & Engineering, Games and Gamification, ICT for Well-Being and Active Aging. ICT Labs in Helsinki is focused on cloud services, smart spaces, digital cities, smart traffic and grids and data security. EIT is technology-driven and conducts university activities such as research, education and innovation.

What do you see as the main aims of Horizon 2020?

Encouraging greater research collaboration is the key objective of Horizon 2020. The framework programme aims to integrate research and innovation efforts towards entrepreneurship as well as encourage smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and job creation. Horizon 2020 also helps implement the Innovation Union and promote European Innovation Partnerships, even as PPPs, which engage developer communities, social networks and citizens.

What ways is Horizon 2020 helping to develop the EU’s innovation eco-system and create an entrepreneurial society?

KICs are one area where collaboration is already very active and well established. The EU will be forming several new consortiums and I really support that. They are good collaborative arrangements that engage companies, academia and public agencies – this is a really positive development for universities. There are also many other collaborative RDI networks in Europe, such as ENoLL, innovation cities and regional innovation networks.

However, I haven’t really seen yet how Horizon 2020 really integrates an entrepreneurial aspect within the research and innovation framework. We should have pre-market experimentation and piloting for understanding and patterning demand, market and user behaviour for scalability and efficiency. When it comes to PPPs, they should definitely be capable of providing positive outcomes in terms of entrepreneurship and creating new firms, markets and even industries. PPPs could operate more under non-profit or ‘tolerance-based’ experimentation funding for new ventures and social and economic activities; they may not need to be subject to short-term business pressures like the corporate sector.

To what extent will Horizon 2020 help improve Europe’s competitiveness in RDI compared to other countries?

Europe is now lacking in R&D funding (as a share of R&D from GDP) compared to the USA and Japan. China is also putting a lot of emphasis on RDI, particularly focusing on energy and sustainable development. After Barack Obama won his second term, I think American universities and the corporate sector made major investments in R&D. There we are seeing investments in new energy sources and systems, as well as in renewing ICT, traffic and other infrastructures. Europe is facing tough competition and that’s why Horizon 2020’s budget should be seen as a very strategic investment from the viewpoint of the continent’s global competitiveness. I think that the EU should now show the world that we are serious innovators and committed to R&D.

Horizon 2020 was originally anticipated to receive an estimated €80bn in funding from the European Commission. This could now drop to around €71bn. What consequences do you think this could have on research and innovation?

There are some worries regarding the Horizon 2020 budget. The original budget of €80bn is now likely to be cut and it may mean that, in terms of research and innovation funding, a cut in long-term growth opportunities and transformational change opportunities. If the budget is cut a lot, it will also mean that the traditional scientific and technological beneficiaries and corporates receive the most attention because they are the ones that are organised when it comes to bidding for funding. There is a tendency that those that are well-connected and know the European procedures best are likely to benefit the most. There is a tendency to do more of the same.

At a recent Horizon 2020 research day at my university, I learned from the representatives from the European Parliament about the H2020 budget. The Parliament originally anticipated the whole budget for research and innovation would be €100bn. It was then €80bn, and now it’s even less, which is worrying. If the Parliament is not able to change the budget for Horizon 2020, it may mean that we are ending up helping more traditional R&D and we wouldn’t really see the opportunity of making some new developments to take place, certainly within the Societal Challenges pillar.

How does Horizon 2020 better address the societal challenges facing Europe compared to FP7?

I think Horizon 2020 is on the right track. The Societal Challenges pillar is a unique new opening with a lot of potential. FP7 had the Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme and a more ‘silo’ and technology domain-driven structure. Horizon 2020 is more horizontal, integrated and holistic – provided that we make it to be like that! The framework also addresses many of the key challenges that Europe and the world is facing.

As I said earlier, the problem may be the implementation. If the Horizon 2020 budget is fundamentally cut there may be a tendency to use money to fund competencies that we already well organised.

Societal Challenges is a new priority and it needs major attention on how to organise and implement the strategic research objectives under the pillar. There is a lot of groundwork that still needs to be done and it may not result in what we had envisaged. If we do not solve this challenge, the pillar’s funds may remain underutilised. I think that there is a new strategic role for member states, cities and regions to take in the initiative.

With the structure of Horizon 2020 now largely confirmed, to what extent do you believe social sciences research is adequately addressed?

I see that besides science, technology and corporate RDI, we need to learn to invest in societal challenges and consequently in structural transformations – this means investing in new types of socioeconomic growth and structural dynamism. Horizon 2020 offers an opportunity for new dynamism that also mobilises people, SMEs and other players for entrepreneurial collective action – even in the field of social enterprising. I really feel that we should positively look at the opportunities to create new firms and support SMEs to grow internationally. However, we should also learn to incorporate humanities and socioeconomic sciences and into Horizon 2020 RDI programmes, even though this means breaking away from old traditions and divisions of labour.

What are your thoughts regarding the creation of the Horizon 2020 advisory groups?

The EU has a long tradition of using advisory groups and experts through different means and mechanisms in the RDI programmes. Concerning Horizon 2020, my immediate impression is that the Commission aims at making the Horizon 2020 activities much more collaborative. I have understood that the Commission experiments with an open-mind in developing wide and competitive forms of participation in the programmes; both bottom-up and top-down forms with member states, firms, regions, public agencies and even research and developer communities and citizens and I really welcome this. The challenge though is how to make it happen and that’s why I really appreciate the Commission setting up advisory boards and workshops, creating a more inclusive bottom-up approach.

Horizon 2020 offers the ability to improve open and participative development in European societies; together we can make our societies and the world a better place to live.

Professor Seija Kulkki