Cat’s genome reveals domesticated variances

A research investigation part-funded by the European Research Council has provided new information on the differences between wild and domestic cats.

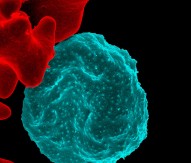

The genome of the cat was analysed by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri, in the United States. Comparing the genomes, the researchers found specific regions of the domestic cat genome had differed significantly. The scientists found changes in the domestic cat’s genes that other studies have shown are involved in behaviours such as memory, fear and reward-seeking. These types of behaviours, particularly those when an animal seeks a reward, are generally thought to be important in the domestication process.

Speaking about the study, senior author and associate professor of genetics at Washington University, Wes Warren PhD, said: “Humans most likely welcomed cats because they controlled rodents that consumed their grain harvests. We hypothesised that humans would offer cats food as a reward to stick around.”

To better understand characteristics of domestication, the researchers sequenced the genomes of select purebred domestic cats. Hallmarks of their domestication include features such as hair colour, texture and patterns, as well as facial structure and how docile a cat is. Most modern breeds are the result of humans breeding cats for their favourite hair patterns.

To obtain the high-quality reference genome needed for this research, the team sequenced a domestic female Abyssinian cat named Cinnamon. The cat was particularly chosen due to the ability to trace its lineage back several generations. This cat’s family also had a particular degenerative eye disorder the researchers wanted to study.

The team also looked at a breed called Birman, which has characteristic white paws. The researchers traced the white pattern to just two small changes in a gene associated with hair colour. They found that this genetic signature appears in all Birmans, likely showing that humans selectively bred these cats for their white paws and that the change to their genome happened in a remarkably short period of time.

Even though the genomes of domestic cats have changed little since their split from wild cats, the new work shows that it is still possible to see evidence of the species’ more recent domestication. The research appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.